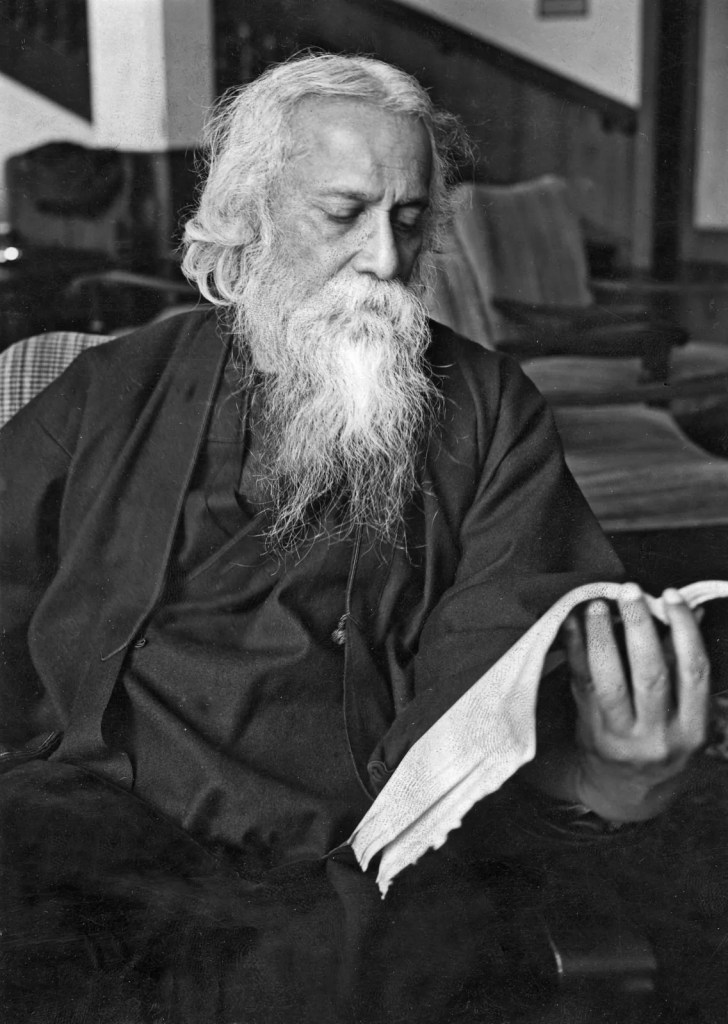

Rabindranath Tagore was the first non-European winner of the Nobel Prize in Literature. He was the only non-European winner until 1945. I chose to read him because I lived in India for a while so I felt a tiny personal connection, and also because I wanted to know what it took for a non-European to get the Nobel committee’s attention back then.

I guess it took a lot–Tagore was accomplished as a poet, song lyricist, short story writer, novelist, essayist, and playwright. He put Bengali art onto the world stage. More than that, as far as I can tell he did most of his own translation work, writing primarily in Bengali and then reworking many of his best poems and stories into English. He was also an educator and political activist. He seems pretty amazing.

Back in 1913 he was most famous in Europe for his poems. Gitanjali seems like his most famous work in English so I started my studies with that. It seems the English version is more a revision of his original Bengali collection combined with a ‘best of’ collection of poems from Tagore’s other Bengali works. I definitely don’t read Bengali but I figure reading Tagore’s own translation and arrangement is a fair way to engage with his work. Gitanjali is a long series of prose poems or verses with a very spiritual, celebratory element to it. Sort of an artist’s offering to his gods. A few quotes will give you a better feel for what the collection is like:

When the hour strikes for thy silent worship at the dark temple of midnight, command me, my master, to stand before thee to sing.

When in the morning air the golden harp is tuned, honour me, commanding my presence.

I have had my invitation to this world’s festival, and thus my life has been blessed. My eyes have seen and my ears have heard.

Gitanjali

He whom I enclose with my name is weeping in this dungeon. I am ever busy building this wall all around; and as this wall goes up into the sky day by day I lose sight of my true being in its dark shadow.

Gitanjali

The sea surges up with laughter and pale gleams the smile of the sea beach. Death-dealing waves sing meaningless ballads to the children, even like a mother while rocking her baby’s cradle. The sea plays with children, and pale gleams the smile of the sea beach.

Gitanjali

It’s all beautiful and evocative. Tagore has a real gift for sensory and emotional detail. If I were more emotional and better at surrendering to the sea of poetry I would love this. I’m not, though. Not that into poetry, I mean. I keep trying to appreciate it and I’ve made progress over the years, but the one hundred or so poetic sections of Gitanjali were a lot for me and by the end I was bored. Those more in touch with poetic feeling than I am can rest assure that there’s much more where this came from, but this was enough for me.

His short stories, though, were something I could really get into. These were lovely. The Essential Tagore I was reading out of had three sets of short stories and I read the one titled “The Hungry Stones and other Stories.” They were varied in topic and style–a couple lovely ghost stories, a few more realistic stories about family relationships and societal issues of Tagore’s day, and one fantasy story that seemed to be an allegory for aspects of the Indian caste system. All of them were written with the same gift for emotional resonance and sensory detail, and all of them had a certain warm and human quality that I loved. Tagore wrote a couple of the stories from a female point of view and though I don’t think he quite succeeded, I appreciated the effort. I didn’t expect a man from over 100 years ago to try to write women with any sense of realism of empathy, so even his partial success was a nice surprise.

After thoroughly enjoying Tagore’s short stories, I utterly failed to enjoy his essays. I’m not even sure I finished one. They’re well written, but the ones I tried were often addressing specific cultural and political topics that now, a century or so later, didn’t feel very compelling. I could see Tagore’s poetic sensibility showing through even in his political essays, but here it was less helpful, making it harder to follow the logic of his arguments and observations. But he did have some keen observations, and in one essay he made some sharp comparisons between the Indian caste system and segregation in the American south; those observations feel relevant for both countries even today. I wouldn’t say the essays aren’t worth a look, but unless you have a real historical interest you might find only the occasional nugget that speaks to you.

The last thing I read was part of My Reminiscences, a sort of autobiography Rabindranath wrote near the end of his life. It’s not really a structured autobiography; it’s more a series of memories or sketches of memorable moments throughout his life. I haven’t read them all but I probably will. They’re warm and human the way Tagore’s short stories are, and full of humor and affection for his younger self. I wonder if my dad read Tagore–he would have loved this autobiography.

Overall, I was delighted to study Rabindranath Tagore. Nobel winners have such a reputation for being sweeping, serious, weighty, and often pretty depressing. This might be true of more recent winners rather than older ones, but I was still pleasantly surprised to find Tagore’s writing so down to earth and full of sympathy and warmth for his fellow humans. My own preference is always for stories over poetry, so of course I enjoyed those most, but it seems Tagore has something for everyone and even after all these years probably deserves more international fame than he’s gotten. If I know anything about the Nobel Prize, which I don’t, he definitely deserved one.

Leave a comment