“He stared at her, groping in a blackness through which a single arrow of light tore its blinding way.”

–Edith Wharton

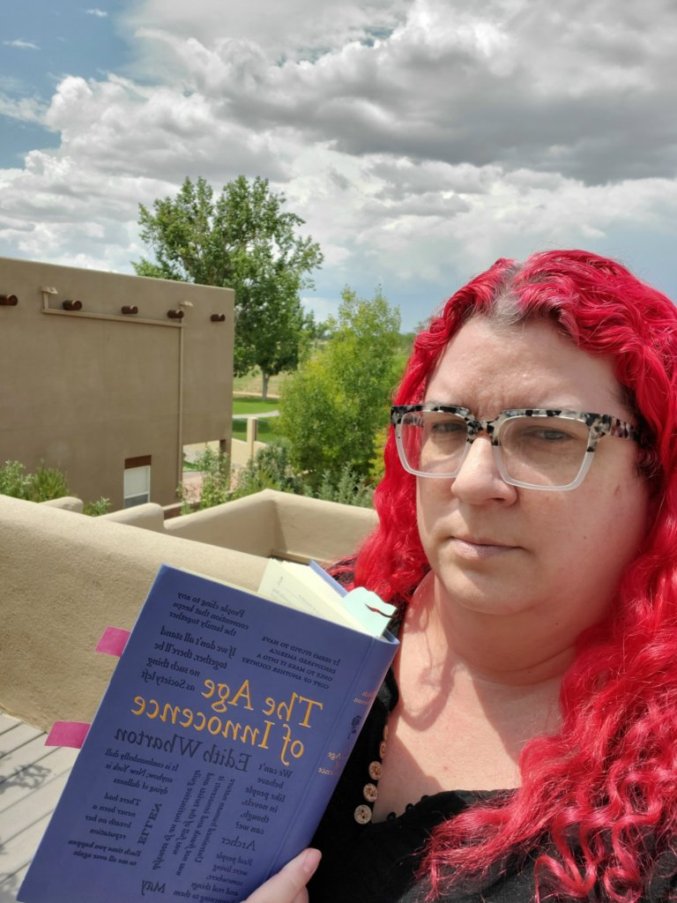

Ever since reading some of Edith Wharton’s elegant ghost stories I’ve thought I should try one of her novels, so I picked up The Age of Innocence at a bookstore during the summer. I admit, I chose this one for its soft faux leather cover as much as anything. I’m not immune to a beautiful book. I also enjoyed the story inside, though.

When I was younger I would not have enjoyed this book. It’s slow paced and very restrained, about a man and woman in passionate love who merely look and sigh and then do ‘the right thing’ according to their straitlaced society’s rules. Not much of a plot when you put it that way, and all the ‘action’ consists of subtle social maneuvering and trying to convey wishes and emotions and decisions without saying anything directly. My young self would have been bored and frustrated without realizing that might be part of the point–the characters themselves are bored and frustrated so you can’t take their journey without feeling those emotions. The book is about the tiny world of New York high society in the time of Wharton’s childhood and how absurdly uptight it all was. By the end of the book it’s clear that even the main character’s children, the next generation of New York society, think this era was absurdly uptight and reject many of the unspoken rules and demands that doomed his budding romance.

As an older, more patient reader I really felt for the characters. Archer, his wife May, and his love interest Ellen Olenska are all, beneath their various passions and prejudices, decent people trying to live good lives and please their friends and family. In spite of their extreme wealth and status they’re very relatable and surprisingly ordinary. To the rest of New York they’re minor celebrities, highlights of the society pages, people with perfect lives. From the inside, however, it feels like they’re living in a small town where your every move is dissected by the local gossips and the wrong move could make all your friends turn their backs on you in an instant. I found myself really sympathetic to their struggles and sad that even the tiny glances and touches Archer and Ellen exchanged were blown up by gossip into a scandalous affair.

I even found myself tearing up at the book’s poignant ending. At the end, it becomes painfully obvious that in any other time and place the story would have turned out much differently. Archer has lived through the end of an era and his decisions would hardly make sense even to his own children. It’s a bittersweet commentary about the speed of change that’s even more true today as things change quicker than ever.

As I expected from Wharton, the writing is lovely and just a bit flowery. When I was young and very focused on contemporary writing I would have found it much too flowery, but reading so many 18th and 19th century novels has shown me just how flowery prose can get. Now, Wharton’s style seems like such an obvious transition between 19th and 20th century styles. Like so many 19th century authors, she loves a good metaphor and lovingly describes architecture and opera gowns, but she keeps it shorter and sweeter than earlier authors and her criticisms have a bit of the sharpness and irony that 20th century authors got so good at.

I also think her perspective might be unique that that change of centuries. Early on, Wharton makes some anthropological references–she’s writing about the era when the “discovery” and study of “primitive cultures” was all the rage–and they’ve got the usual vague colonialist vibes. But she primarily includes them to highlight how cultures all over the world, including the top of New York Society, repeat the same rituals and have the same problems as each other. The references also invite us to see the novel itself as a bit of an anthropological study–to see New York society as an exotic culture with its own weird rules and rituals. I’ve read several late 19th century novels that play on this colonial fear and fascination with ancient cultures and “primitive” tribes, and I’ve seen plenty of 20th century novels that directly explore issues related to colonialism; this one seems to occupy an interesting place of dawning awareness that “exotic and primitive” cultures might not be as exotic and primitive as colonizers wanted to believe. I’m guessing that’s not what 1920s readers were focused on when they read The Age of Innocence but it was an added layer of interest for me as a modern reader.

I generally prefer just about anything to ‘novels of manners’. Even as an older and wiser reader, authors like Henry James and Jane Austen are pretty far down on my list of favorites. My own society’s unspoken rules are confusing and frustrating enough–usually the last thing I want to do is immerse myself in the fine details of another society’s unspoken rules. But something about Edith Wharton just really speaks to me. Maybe it’s her deep ambivalence, sympathetic both to rule-bound Archer and to Ellen Olenska’s breaking of all those rules. Maybe it’s her well-honed writing style. Whatever it is, Wharton has me. No matter how far she is from my usual literary interests, I’ll be coming back to her.

Leave a comment