You write novels. You of all people must know that you cannot choose between them, divide them into categories. They are all useful in their own way.

—Yoko Ogawa

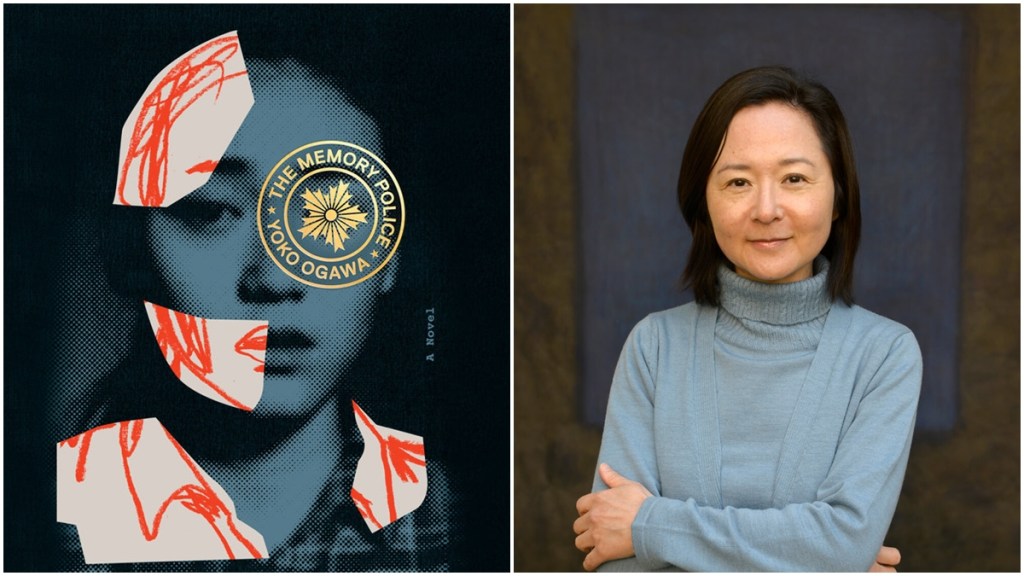

Early in the year I read The Diving Pool, a small collection of stories by a Japanese writer named Yoko Ogawa. I really enjoyed their subtle horror and the way the characters were haunted by their own darker emotions. This summer while we moved I bought one of her novels, The Memory Police. It was weird and sad and I loved it. Though Ogawa has been published in Japan since the 1980s, only a few of her works have been translated into English; The Memory Police was only translated a couple years ago but it was written in 1994.

The story is about a novelist who lives on an island where things disappear. Whole categories of things disappear, like gemstones or photographs or roses. On one level, this island is a creepy totalitarian society–on the morning roses disappear, everyone cuts down their rose bushes and throws all the petals into the river to be washed away, and anyone who doesn’t do this will have their home ransacked and all traces of roses removed. People suspected of remembering officially disappeared things will be found and arrested, never to be seen again.

On another level, the disappearances are much deeper than that. Most people on the island, once a thing has disappeared, quickly forget what that thing looked like or felt like. One of the narrator’s best friends used to run a ferry boat–when boats ‘disappear’ he still uses the ferry as a boat house, still vaguely remembers how fun it was to do maintenance on the boat and drive it to other places, but in a very deep way he just can’t even imagine fixing it up and sailing away to a place where boats might still exist. It’s not just that the memory police would arrest him, it’s that the concept of sailing away is gone even from his mind and heart. The narrator herself has this problem; when things disappear she no longer feels any connection to them, and she’s afraid of the day when novels disappear and her ideas will no longer grow into stories.

The narrator’s editor, however, does remember things when they’re gone. They keep their meaning and importance, and he’s sad to see them lost even to memory. The narrator doesn’t understand how or why this is possible but she decides to help him, hiding him in a secret room lest the memory police find and arrest him.

Through most of the story, right up until novels do indeed disappear, our narrator is writing her latest book. Chapters of her own novel are interspersed throughout the main story. This novel within the novel starts out romantic but ends up quite a chilling horror story. It’s interesting, because the narrator doesn’t seem all that horrified when major things disappear on her island but all that horror she represses in real life seems to come out in her writing. Since she doesn’t see any way out of this disappearing life, she can’t write a way out for the heroine of her story either. The whole novel is very restrained, and the characters’ very passivity makes it much more harrowing to read. By the end it seemed like I was feeling all the horror and tragedy the characters weren’t able to.

As I read, I had the powerful feeling that an American would have written this story very differently. One of my professors once said that Japanese novels usually were more about atmosphere and theme than plot, and that’s certainly true, but here there’s also a world view that’s just profoundly different from what I’m used to. An American would have had these characters plotting to infiltrate the memory police headquarters or escape the island, and if they truly couldn’t they would have at least loudly bemoaned their terrible fate. We would have turned this book into Demolition Man or Minority Report. It’s both difficult and probably really good for me to switch out of this American ‘cowboys and crusaders’ mindset and explore another point of view. I’ve encountered this kind of resignation and sadness in Japanese novels before, especially with Kazuo Ishiguro (though Ishiguro is Japanese and British). There’s a feeling of “I’m just one person, I can’t fight all of history or society alone” that is true and profound and completely foreign to Americans.

No, this story isn’t about beating the odds and coming out on top, it’s about coping with loss. All the characters, including the ones in the narrator’s own book, are dealing with loss in their own ways: by clinging to the past, by cheerfully pressing on, by reaching out and protecting others, or through radical acceptance. This isn’t a self-help book ot a how-to (both very American genres) but a meditation on the fact that we’re always losing things and we’re all trying to cope with the transience of life.

It’s all very dreamlike and laden with beautiful images and sadness, but I still felt connected to the narrator and her friends. The narrator doesn’t have a name, but she has a history and an inner life that made me care about her struggles and fears. I really enjoyed this book and will definitely be looking for more of Ogawa’s work in the future.

Leave a comment